Cover Photo: Indonesian president Suharto, widely regarded as a dictator, with U.S. President Gerald Ford and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger on 6 December 1975, one day before the invasion of East Timor. (Public domain photo). The United States may be capitalist and democratic, but their support for authoritarians beyond their borders throughout history exposes the empty rhetoric of democracy promotion as a policy objective.

Volume 3, Number 1: October 2019 | Essay

Over the last six months I have seen [well-respected] news media dedicate substantial attention to the challenges facing both democracy and capitalism. The first trigger to this wave of discussions seems to be a comment made by Vladimir Putin back in June that liberalism “has become obsolete.” This has prompted mainstream liberal commentators – such as Martin Wolf, lead economic analyst at The Financial Times; Larry Diamond of the Hoover Institution and writing for Foreign Affairs; and The Economist, among others – to argue that capitalism and democracy are mutually supportive. The second trigger to this wave of discussion has been the ongoing protest movement in Hong Kong, prompted by the highly publicized and controversial extradition bill that the Hong Kong government attempted to push through, but has since withdrawn. According to some, this event represents a defense of democratic principles against an ever-increasing authoritarian threat, whether only perceived or actual, from the mainland Chinese government. According to others, the resistance movement goes much deeper and is based on a rejection of the billionaire capitalists that have made home ownership all but out of reach for millennials as well as an increasing sense of hopelessness about the future in a city/state that most clearly exemplifies capitalist principles and whose “democracy” has effectively been taken over by said billionaires. Are the protests a defense of democracy, a rejection of capitalism, or both? If capitalism erodes democracy, then it is both.

I will argue that capitalism and democracy can coexist, but they are not mutually supportive. The only way for these two to coexist is if there are strong democratic institutions in place along with active public participation, which serve to constrain the natural tendencies of capitalism toward wealth and power concentration. Capitalism meanwhile seeks undermine democracy by discouraging the public from participating in economic and political affairs, through a variety of mechanisms of filtering information and distraction, primarily done through a sophisticated set of ideological institutions designed to achieve a system of thought control, even within a “free society.” I will also show that capitalism and democracy can coexist internally, while supporting authoritarianism externally. Given the globalized economy we all find ourselves in, this second point is particularly important and is a major omission from much of the current political commentary on the issue. On a global scale there is a democratic deficit, which, in line with my first point, means there are no institutions in place to constrain the natural tendencies of capitalism and we find the wealth extraction and concentration of power translates into a positive feedback in which the growing inequalities and lost opportunities for the majority will continue to increase dramatically.

This global democratic deficit also weakens democracy at home as it promotes a race to the bottom, due to the importance of capital for growth and development. As long as capital is mobile, owners can threaten to relocate if governments implement policies or reforms than the public wants, but which undermine growth and hence returns. So as long as a domestic economy is capitalist, it is only a matter of time before the democratic institutions are severely weakened and that is what I see happening in the United States and Hong Kong, both classic examples of capitalist systems. We see in states like Australia, France, Hong Kong, and America governments increasingly using repressive anti-protest laws as more people take to the streets to demand action on climate change, democratic reform, and the negative impacts of globalization. I borrow the following quote from Sam Wainwright (2019, October 11) at the Australian Green Left Weekly, “it will not take long for people to see that the essential function of the police is not to `uphold the law’ but to protect the rich and powerful. In this country [Australia], that means the fossil fuel capitalists who use their wealth and power to buy politicians.”

Underlying Concepts and Clarification

From the development literature, such as the work of Daren Acemoglu and James Robinson as well as the work of Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen, institutions matter for improvements in well being. It is suggested that both political and economic institutions must be inclusive in order to realize the objectives of development such as education attainment, health, livable environments, and the ability to participate in social life – economic and political affairs, both of which are means and ends themselves. The long run stable equilibrium is extractive political and economic institutions, because once you have extreme inequality, barring a natural catastrophe, it is incredibly difficult without mass movements, widespread destruction, or revolution to reverse back to inclusivity.

Democracy by definition is inclusive. It stems from the Greek word dēmokratía, which is government (krátos, “power, rule”) by the people (dêmos). However, in practice what is often labeled as democratic is actually far from it and the degree to which a society is democratic is constantly changing. Republics, though often associated with democracies, are not technically democracies. Positions of political power within a republic can be attained through democracy, oligarchy, autocracy, or some combination of the three. The United States is a constitutional republic, which does not automatically imply it is democratic. However, according to Amartya Sen, some of the characteristics of the American system which contributes to its inclusivity is how the permissive role of political and civil rights – allowing open discussions and debates, participatory politics, and unpersecuted opposition – applies over a wide domain. However, should examples like the United States and Hong Kong really be considered democratic when their systems are bought and increasingly controlled by oligarchs, thanks to the rising inequality as a consequence of deregulation, privatization, and free capital mobility, which are key staples of capitalist institutions?

In contrast, capitalism by definition is not so clearly inclusive. Part of the problem is that no single clear definition of capitalism exists (see note 1), so it can be easily twisted and sold as inclusive and even argued to support freedom and democracy. The reason for this lack of consistency lies in the complex nature of such a political-economic system, because it is not simply an economic system, but rather one in which the political system is inextricably linked. Because of its complex nature, it would take too long to fully explain here. I will resort to a simplified description, which should suffice to clarify enough so that we can understand the connections to democracy.

I would describe capitalism as a complete set of political, economic, and social institutions which comprises a system that prioritizes the interests of capital owners and investors – people who seek to earn income passively, not necessarily entrepreneurs and small-medium business owners who work full-time with the business operation – above all else. This can be seen in the rule of law. Who writes the laws? In whose interest are the laws written? According to Glenn Greenwald in his book, With Liberty and Justice for Some, America has evolved into a two-tiered justice system which applies different standards and enforcement to the haves and to the have-nots. Those who perform an institutional role – whether it be in finance, marketing, the university system, media, entertainment, government, among many others – will be compensated relative to how well they serve the system which is designed to produce [passive] profits for those who own assets. The social institutions [those which influence social norms] place the wealthy on a pedestal to be revered and something to aspire to – the so-called “American Dream” – and is what motivates people to internalize the values of the system. At the same time, words like “class” are rarely used in public discussion, because people have been conditioned to ignore class divisions. Commonly attributed to John Steinbeck, poor Americans do not see themselves not as exploited proletariat, but rather as temporarily embarrassed millionaires. Hence, the system itself is rarely challenged.

But, how inclusive is capitalism and why should it be expected to promote democracy? Well, in a system designed to serve the interests of investors first and foremost, it should be pretty obvious. What is it that investors want? Why should they care about democracy if they, as the wealthiest in the society, are a minority? Is it possible that democracy could even jeopardize their interests? [See the Crisis of Democracy discussion below.] I would argue that capitalism is extractive by design, but its extraction capacity in a free society will be limited by the public’s tolerance for the system. Those for whom the system works will continue to see their benefits increase as long they remain the minority while the majority works in order to produce the benefits which can be extracted. Take for instance the quote from Billy Tung, a 28-year old accountant from Hong Kong, who lives in a small subdivided flat shared by six people, and whose boss expects him to work most Saturdays and Sundays, “I don’t want to spend the next ten years working just to give it all away to Hong Kong real estate developers,” (Lindberg et. al., 2019).

What evidence exists to demonstrate investors’ concern for democracy? A recent quote from the Guardian, Verna Yu suggests that “Investors’ confidence in Hong Kong’s rule of law and freedom of speech, the two cornerstones of Hong Kong’s status as a global financial hub, are in jeopardy.” I accept that capitalists (investors) do care about rule of law [at least as far as protecting their investments goes], yes; but not workers’ rights so much and certainly not freedom of speech. That is why capitalists will support stable authoritarianism over “dirty democracy.” Stability is what matters. So which side are the investors really on? They’ve had no issues investing in China up to this point, because the Chinese government has given foreign investors free reign to exploit in their SEZs (special economic zones). The same is true of investors in Myanmar, who turned a blind eye to authoritarian rule for decades. I assume there must be free speech in these SEZs. Yeah, right. The list of examples to this point is very long and provides sufficient counterexamples to reject the claim for investors’ (and therefore capitalism’s) concern for democracy.

Another point of reference when it comes to stability and the interest of investors can be seen from the brief period of Thai democracy in the 1970s. According to Baker and Phongpaichit (2014), “The political excitement of the 1973-1976 era disrupted business. After October 1976, the prime minister, Thanin, hoped the return of firm rule would also mean the return of foreign investment.”

In Chomsky and Herman’s work, The Washington Connection and Third World Fascism (1979) they discovered a systematic positive relationship between U.S. aid and human rights violations (use of torture, death squads, political prisoners, etc). While at the same time, these are also correlated with an improvement in the investment climate (labor repressed, tax laws eased). This is exactly what Kennard and Provost (2016) reported is happening in the SEZs of Cambodia and China.

Now why is this not well known in the West; and particularly less well-known in America itself? That fact can be understood better when you begin to examine how a propaganda system works in a democratic (or free) society. Since capitalism’s extraction capacity in a free society will be limited by the public’s tolerance for the system, that tolerance (or consent) has to be manufactured; since, if people actually understood how it works, most people who work for the system, except for maybe those at the very upper end, would likely reject it.

What the Simple Correlations Omit

In this section, I turn to what I consider interesting examples of the propaganda model in action. The model I will explain more in the following sections, but first I introduce the cases. While the information presented in these articles may be factual, depending on the quality of the index measures used; the interesting thing to look for when trying to identify bias is what is left out, either deliberately or unintentionally.

Let us first take a look at Martin Wolf’s July article in the Financial Times. Here he presents the reader with two simple graphs. The first graph shows a positive correlation between economic prosperity (in terms of per capita income) and a composite index of liberalism – combining the World Bank’s “voices of accountability” measure and the Heritage foundation’s “index of economic freedom.” The second graph shows a positive correlation between “voice and accountability” and “economic freedom.” These correlations are meant to imply that the less we restrain capitalism, the more democratic the society will be, along with higher prosperity.

My first point of criticism is that these correlations tell us nothing about the distribution of the prosperity. Also, how do these measures change over time and at what point in time are they observed for the sake of this analysis? Take Chile, for example. Does the “voice and accountability” measure consider Chile during the Pinochet dictatorship or after the shift toward a superficial democracy? Inequality soared under Pinochet, even while growth was impressive, because the gains were going to the elite who had opposed the reformist policies of Salvador Allende, supported the coup in 1973, and were supported by the United States.

In both of Wolf’s graphs, the unit of observation is problematic here. Take for example, two countries, The United States and Indonesia under the Suharto dictatorship. One would observe the United States as both prosperous and liberal, while Indonesia is not-so-prosperous on average [yet growing] and illiberal. This would be consistent with the correlations in the graph provided; however, it fails to link the United States support for the Suharto dictatorship. Well connected Indonesian elites and foreign investors become obscenely wealthy, despite the low average standard of living, thanks to the investment opportunities that were opened up and protected by repressive policies, backed financially and militarily by the United States. In another case, according to Baker and Phongpaichit (2014), “In Thailand, the United States underwrote dictatorship, but at home it exemplified ideals of liberalism and republicanism,” (p.166). Furthermore, Chomsky and Herman (1979) confirm this point by stating, “In the 1973-1976 period of weak democratic rule [in Thailand], terminated by a military coup, one searches in vain even for verbal support by the United States for the new democracy,” (p.229). This means that the United States can be democratic at home, but support fascism abroad in order to open up and protect investment opportunities for its own elite interests. So why is this point left out of their discussion?

The next article I would like to look at is from a June issue of The Economist, published in their column Free Exchange, which asks the question how compatible are democracy and capitalism. It is pretty clear from their subheading – which reads, “Economic stress and demographic change are weakening a symbiotic relationship” – that they have concluded that capitalism supports democracy. However, they never provide a convincing argument to explain the mechanism by which such a supportive relationship emerges other than looking at simple correlations. They ask, “if capitalism and democracy are such uneasy bedfellows, what explains their long co-existence in the rich world?” The writers seem to have missed my above point about external influence. The article does refer, albeit briefly, to thinkers such as Thomas Piketty, who argued quite convincingly that “inequality naturally rises in capitalism and that political power becomes concentrated alongside economic power in an unstable way.” Yet, they seem unconvinced, even while ending their article with the following line: “the authors may have underestimated the corrosive effect of inequality. Threatening to leave is not the only way the rich can wield power. They control mass media, fund think-tanks and spend on or become political candidates.” While acknowledging these factors, why is it still seemingly so difficult for them to understand their flawed logic? I can only shake my head in disbelief.

The question that remains is whether or not these oversimplified analyses and conclusions drawn are performed out of ignorance [we’ll refer to this as internalized values later on], institutional constraints, or a deliberate attempt to mislead. I believe that if the writers can convince the readers that capitalism will bring democracy, then it serves as useful propaganda for capitalism, which is by design antagonistic to the interests of the majority of the population who earn their livelihood through wage income.

Globalization’s Impact on Democracy

What are the global economic institutions and what are the global political institutions? Who writes the rules? In whose interest are the rules written? How are the rules of the global economy written? Who enforces the rules?

Global economic institutions are relatively easy to identify. They include global financial markets and lending institutions, such as the IMF and World Bank. Global capital is highly mobile. Global markets for goods, services, and labor are also relatively easy to identify. While goods are relatively mobile, the least mobile is labor for obvious reasons relating to immigration laws, language barriers, cultural differences, relocation costs, and local ties. The greater the degree of mobility, the easier it is to leverage one’s position against the lesser mobile. This gives financial capital an enormous advantage; an advantage which the owners of capital can exploit to influence the rules of game to further reinforce that advantage.

When it comes to political institutions there are intergovernmental organization such as the World Trade Organization and the United Nations. There is no effectively binding overarching governing structure, but rather a set of treaties and bi- and multi-lateral “trade agreements” related to market access, regulations, and enforcement of property rights. These “trade agreements” are essentially corporate/investor-rights agreements, as the “trade” part is a propaganda word which short-circuits thinking. People hear the word trade, they assume trade is good, and they stop thinking. However, the primary focus of these agreements is on intellectual property rights provisions and other monopoly rights so the owners can collect rents. The agreements also give corporations, working on behalf of investors, the ability to defang governments’ abilities to pass regulations – such as environmental and labor protections – which infringe on the expected profits of investors. The World Bank is now even helping investors shop around for favorable laws, known as “law shopping,” as explained by law Professor Alain Supiot (2019) speaking at the International Labor Organization. He points out that you cannot have “law shopping” and rule of law at the same time [see note 2].

Who writes the rules and in whose interest are the rules written? Given that all trade agreements are written behind closed doors with no public scrutiny and input, who is present at the table? These are often captains of industry, primarily corporate leadership and financial institutions, meeting with national governments and in some cases local governments as well. If we know who is at the table, it becomes pretty clear in whose interests the rules are written. They represent the global investor class and their interests – which are clearly not about democracy, given the fact that the public is all but excluded due to the lack of transparency.

Who enforces the rules? The two key areas of leverage are military power and financial control. In this regard, the United States plays a central role in the defense of these interests by waging economic warfare through sanctions, embargoes, and influence in multilateral lending institutions and global financial markets; indirectly through financial support for coups and regime change efforts of democratically elected leaders who pursue paths independent of U.S. interests; financial aid and support for military dictatorships and authoritarians who align with U.S. interests and who can maintain stable investment climates; and directly through military invasions for strategic control of resources and areas to defend investor interests.

Considering this enforcement role, let’s look briefly at two of America’s most controversial military interventions of the past fifty years – Vietnam and Iraq. Military historian Victor Davis Hanson of the Hoover Institution – in a video from PragerU, which I do not recommend you watch – explained why America fought the Vietnam war (1964-1975). I want to draw attention to the phrase he used. In the video he claimed the purpose was the “defense of freedom in Asia.” In the case of Iraq, “Operation Iraqi Freedom” was the slogan used to promote the illegal invasion of a sovereign nation which did not pose an external threat to the United States. One would be forgiven for seeing these phrases as laughably blatant lies, assuming you’ve studied the history of American foreign policy. However, there is a subtlety to these phrases, which makes them technically not false and it revolves around the word “freedom.” It is important to point out that “freedom” does not necessarily imply democracy. The important question to ask is, “freedom for whom?”

To answer that question and maintain consistency with the historical record, we must logically conclude that it means “freedom for investors and other capitalist interests.” If we change those slogans to read, “Defense of Freedom [for investment] in Asia,” and “Operation Iraqi [investment] freedom,” it becomes apparent that the U.S. military plays an enforcement role for the rules of the global capitalist system. In the case of Iraq this was clearly a win for investors in companies like Halliburton and other defense contractors brought in to rebuild a war-torn country, not to mention petroleum company investors. In Vietnam, it was a bit more complicated, but it was part of the broad investment strategy for Southeast Asia as a whole, in particular Indonesia, which was a great material prize [see note 3].

To keep people from understanding that U.S. foreign policy actions are not carried out in the interests of the populations of the United States and abroad requires a sophisticated propaganda system. Sadly, people continue to buy this propaganda when it comes to the case of Venezuela. Even [now former] national security adviser John Bolton went on Fox Business and stated their interest is in getting American companies to be able to produce Venezuelan oil. Their calling Maduro a [brutal] dictator and their claims about concern for democracy should be easy to see through, yet, many intellectuals still fail to see it.

Propaganda and America’s Role in Democracy Promotion

To many, the United States is still viewed as the primary example of a system which exemplifies both democratic and capitalist principles and as the defender of such principles on a global scale. While I accept the claim that the US defends capitalist interests, I am certainly not alone in rejecting the claim that the U.S. defends democratic institutions abroad. Capitalist interest have always taken priority over democracy, even to the point of American aid being used to support dictatorships which align with U.S. [economic] interests. Why is this view still so strongly held, despite the mountain of evidence to the contrary?

To maintain a stable democracy which is compatible with capitalist interests, it is necessary to maintain a relatively passive, politically apathetic, and effectively disenfranchised population. Keep people sitting alone, plugged into devices which entertain, divert attention, provide filtered information, and encourage consumerism is one way of achieving this – in the past it was the television; today it is the smartphone. An even more effective mechanism is to get people to internalize the right values, having been properly socialized to the values that align with elite interests. This is usually the role of elite education system. Once the appropriate values are internalized, people will not even challenge the underlying institutional structure. This internalization process requires a sophisticated system of propaganda and thought control made up of the ideological institutions which include the media, education, and religion, just to name a few.

One of the main functions of the propaganda system is to obfuscate the truth about American foreign policy. This is because America, despite its reputation for domestic gun violence, was historically as pacifist population. It was not until the First World War, when the Committee on Public Information (otherwise known as the Creel Commission) – an independent agency of the United States government – was created to influence public opinion to support US participation in World War I. Since then and especially since World War II, patriotism has permeated American society and which is perpetuated by jingoist slogans which glorify war and the military. The U.S. military runs extensive recruiting campaigns which are now even part of American professional football games [NFL].

When you have a center of power, there is often a set of doctrines which determine essentially how the institutional structure is supposed to operate – this can be referred to as the “state religion” or “orthodoxy.” A simple description of how this system of thought control works was describe rather simply by George Orwell in his proposed preface to Animal Farm, “The Freedom of the Press,” which was suppressed and only came out about thirty years after he wrote it. What he suggested is that, first, there is an orthodoxy that all right-thinking people internalize as they make their way through the elite education systems, which teach socialization and how to behave; and if you don’t adapt to that, you are out. Second is that the press is owned by wealthy men who only are willing to publish ideas that do not explicitly contradict or undermine their interests. A much more complex explanation can be found in Herman & Chomsky’s, Manufacturing Consent (1988). Those who make it into positions where they can actually influence public opinion – media and universities – usually have only made it there because they have internalized the right thoughts in order to ascend through the institution. Because of this, they do not even need to be told what not to say, so they feel as if they are free to be critical, without ever questioning the underlying institutional structure.

Before hearing this, one might have expected that the least educated are likely to be the most indoctrinated. This is, however, not the case. It turns out that often the most indoctrinated are the intellectuals who have gone through the elite education system and internalized the right way of thinking. Their consent is crucial to the system because their institutional role is to serve as the “secular priesthood” who promulgate the “state religion.”

The “secular priesthood’s” objective [to use Isaiah Berlin’s term] is to present not only the official state doctrine, but also to capture the entire spectrum of possible thinking. Chomsky has explained quite well in many of his public lectures the way in which the system works to this effect: include those who put forth the official doctrine and those who are identified as fierce “critics” in order to define the parameters of acceptable debate. That entire spectrum of opinion must meet one condition: the tacit presupposition that runs across the entire spectrum must be the official doctrine of the state “religion.” In the case of the United States, the debate over foreign policy takes the form: the orthodox scholars and the realists. Throughout the whole debate the same premise is presupposed: the unique benevolence of the United States and its lack of concern for material interests of any social group. The effectiveness of such a system lies in the challenge that in order to understand the system of thought control you not only need to dismantle the system of government and its propagandists, but you have to take apart the whole spectrum of debate. You have to examine what lies behind the critical rejection of the official position as well as the official position itself.

Now I would like to turn to an example of this type of indoctrination which jumped out at me when I was reading Larry Diamond’s recent article in Foreign Affairs this past summer. In his article, Diamond parrots the official party line suggesting that the United States is concerned with promoting democracy. Here he writes:

A quarter century ago, the spread of democracy seemed assured, and a major goal of U.S. foreign policy was to hasten its advance – called “democratic enlargement” in the 1990s and “democracy promotion” in the first decade of this century.

Larry Diamond, Democracy Demotion, p.18

…

Ultimately the decline of democracy will be reversed only if the United States again takes up the mantle of democracy promotion. To do so, it will have to compete much more vigorously against China and Russia to spread democratic ideas and values and counter authoritarian ones. But before that can happen, it must repair its own broken democracy.

What evidence does he show that spreading democracy was a major foreign policy goal? At first, when I read this, I assumed he has never read any of the internal planning documents from the post-war years detailing the actual “grand area” strategy of U.S. foreign policy and its objectives; which is understandable, since many were not declassified until the 1970s and perhaps never came across them since. They are, for reasons which should be obvious, not widely circulated. One such document was written by George Kennan, who was instrumental in the planning and formation of Cold War programs and institutions, notably the Marshall Plan. Kennan was also among the foreign policy elders known as “The Wise Men.” While I would have expected Diamond to at least be aware of the history of U.S. interventions at this point in 2019, near the end of the article Diamond actually refers to George Kennan! He writes what appears to reflect the public’s perception of Kennan:

Kennan urged the United States to grasp with clarity the diffuse nature of the authoritarian threat, strengthen the collective military resolve and capacity of democracies to confront and deter authoritarian ambition, and do whatever it could to separate the corrupt authoritarian rulers from their people.

But Kennan also understood something else: that the greatest asset of the United States was its democracy and that it must find the courage and self confidence to adhere to its convictions and avoid becoming like those with whom it is coping.

Larry Diamond, Democracy Demotion, p.25

..

Today, as the United States confronts not a single determined authoritarian rival, but two, Kennan’s counsel deserves remembering.

But if one actually reads George Kennan directly from this internal memo to Secretary of State and the Under Secretary of State, one reads about a much different set of policy objectives which runs counter to that of “democracy promotion” official line. I have selected some direct quotations from the section related to U.S. policy in the Far East. So when we think of U.S. support for military regimes in Thailand, Suharto in Indonesia and his domestic repression and the invasion of East Timor, and Marcos in the Philippines; helping the French recolonize Vietnam (1946-1954), splitting the country in two, rejecting the Geneva Accords’ call for reunification and nationwide elections in 1956, and supporting dictatorships in the south, such as Ngo Dinh Diem and the “pacification” efforts leading up to direct involvement; and then actually waging the Vietnam War (up to 1975) resulting in somewhere between two and four million people killed – which all seem contradictory to “democracy promotion” – it becomes clear that the goal was control over resources, opening up markets, and protecting investment opportunities. Here is part of George Kennan’s memo:

…we must be very careful when we speak of exercising “leadership” in Asia. We are deceiving ourselves and others when we pretend to have the answers to the problems which agitate many of these Asiatic peoples.

Memo PPS23 by George Kennan, 1948 (emphasis added by author)

Furthermore, we have about 50% of the world’s wealth but only 6.3% of its population. This disparity is particularly great as between ourselves and the peoples of Asia. In this situation, we cannot fail to be the object of envy and resentment. Our real task in the coming period is to devise a pattern of relationships which will permit us to maintain this position of disparity without positive detriment to our national security. To do so, we will have to dispense with all sentimentality and day-dreaming; and our attention will have to be concentrated everywhere on our immediate national objectives. We need not deceive ourselves that we can afford today the luxury of altruism and world-benefaction.

…

In the face of this situation we would be better off to dispense now with a number of the concepts which have underlined our thinking with regard to the Far East. We should dispense with the aspiration to “be liked” or to be regarded as the repository of a high-minded international altruism. We should stop putting ourselves in the position of being our brothers’ keeper and refrain from offering moral and ideological advice. We should cease to talk about vague and—for the Far East—unreal objectives such as human rights, the raising of the living standards, and democratization. The day is not far off when we are going to have to deal in straight power concepts. The less we are then hampered by idealistic slogans, the better.

In his attempt to expose the propaganda, independent journalist John Pilger produces documentaries which highlight the historical record of American and British foreign policy interventions. One of his first documentaries, Vietnam: The Quiet Mutiny (1970), showed the internal resistance of the troops who were refusing to fight. The anti-war movement at home in the United States and the public withdrawal of support for the Vietnam War is what ultimately brought the direct conflict to an end and final withdrawal in 1975. The peace movement, which included the Vietnam Veterans Against the War, promoted the idea that the war was immoral and that the U.S. had no right to be there in the first place. This way of thinking was outside the parameters of acceptable debate and was evidence that the propaganda system was breaking down, much to the dismay of leading elite scholars. Today, mainstream public intellectuals, like military historian Victor Davis Hanson of the Hoover Institution and Bruce Herschensohn of Pepperdine University who have both been featured in misinformation youtube videos from PragerU, continue to parrot this official narrative of the Vietnam era, despite plenty of additional information from declassified planning documents and the internet, which makes their claims laughable. Their primary position is to blame losing the war on this anti-war movement and lack of public support for the war effort, all under the assumption the U.S. was justified in waging the war in the first place.

The Trilateral Commission’s report of 1975, The Crisis of Democracy, points out that during the period of the late 1960s and early 1970s there was an excess of democracy, which, in their words “the pursuit of democratic virtues of equality and individualism has led to the delegitimation of authority generally and the loss of trust in leadership” (p.161) and that the “institutions which have played a major role in the indoctrination of the young in their rights and obligations as members of society” – the family, the church, the school, and the army – have essentially lost effectiveness (p.162). Of course this report reflects elite perspectives from the three centers of economic power, America, Europe, and Japan; and the message is clear that too much democracy means that “the effectiveness of all these institutions as a means of socialization has declined severely” and will limit America’s ability to maintain international trade, balanced budgets, and “hegemonic power.” They were concerned that the authority [structure which defends their interests] has been challenged not only in government, but also in business enterprises, schools and universities, professional associations, churches, and civic groups. “The success of the existing structures of authority in incorporating large elements of the population into the middle class, paradoxically, strengthens precisely those groups who are disposed to challenge the existing structures of authority [power].” This report is a prelude to the reactionary policies, specifically in the Carter administration, from the liberal [critical] wing of the state capitalist elites.

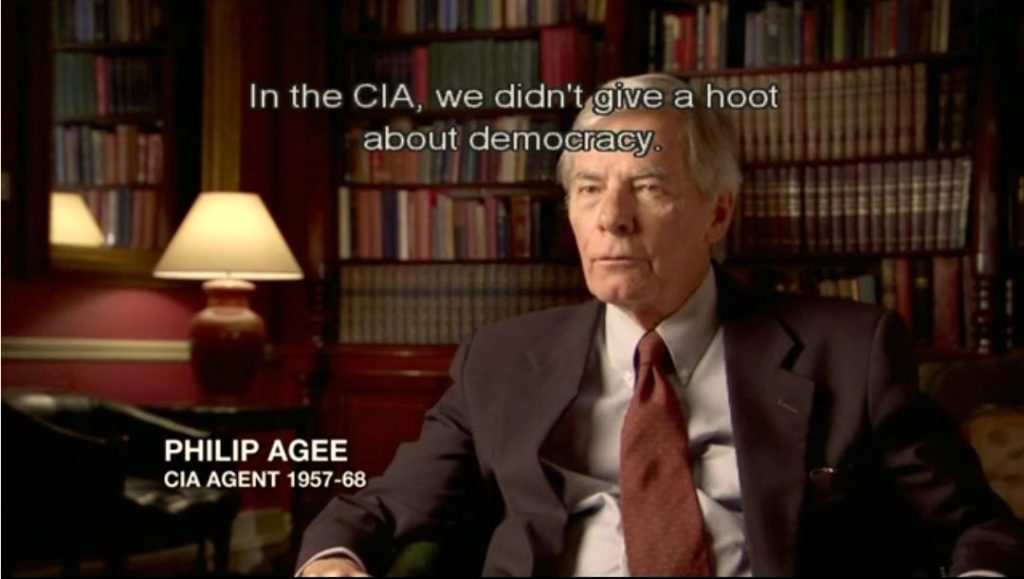

In his more recent (2007) documentary, The War on Democracy, John Pilger presents some of the missing history of economic development and U.S. foreign policy in Latin America. The film highlights Venezuela, Guatemala, Chile, El Salvador, and Bolivia. Pilger interviews former CIA agent Philip Agee (1957-1968) and he provides a further contradiction to this mainstream narrative. This is what he had to say about American concern for democracy in its foreign policy objectives:

In the CIA, we didn’t give a hoot about democracy. I mean, it was fine if a government was elected and would cooperate with us. But if it didn’t, then democracy didn’t mean a thing to us, and I don’t think it means a thing today.

Philip Agee interview – John Pilger’s documentary, The War on Democracy (2007)

…

The true goal of the United States government is control. They feel that if they did not control the governments of Latin America, the someone else would and the principle of government by the people, for the people, and of the people, that is, uh, just…that’s just silly.

Finally, back to Martin Wolf, we can see from his article how he has also internalized these values – assuming the U.S. to be the most influential defender of democracy, while never really questioning the cause of the democratic decline. “In Freedom in the World 2019, the independent US watchdog Freedom House reported a 13th consecutive year of decline in the global health of democracy. This decline, it noted, also occurred in western democracies, with the US — the most influential upholder of democratic values — leading the way,” (Wolf, 2019 July). If he knew the history of U.S. foreign policy, would he still write this?

Interestingly, Martin Wolf wrote a more recent article in the Financial Times (2019, September 18) titled, “why rigged capitalism is damaging liberal democracy.” While he correctly identifies the problem that many commentators have failed to recognize or admit, what he describes as “rigged capitalism” is exactly what capitalism is – a set of political, economic, and social institutions designed for the benefit of investors and the ownership class. The “rigged” is redundant, because that is why the rules of the game are written the way they are. He correctly calls out the finance sector. “Finance also creates rising inequality.” He cites a study by Thomas Philippon who found that “rents” accounted for 30-50 per cent of the pay differential between finance professionals and the rest of the private sector – which , in my view, is evidence which shows you are paid according to how well you serve the system, not your social contribution. Finance is key to the wealth extraction of capitalism. Wolf also points to the rent extraction of corporate management and market concentration – all good for investors, by the way. None of them are complaining, as long as the majority is complacent. Only under popular pressure have investors and corporate leadership recently started to self-reflect on shareholder value theory.

Perhaps Wolf’s misunderstanding stems from the fact that no clear collectively-understood definition of capitalism has been adopted. Or is it that Wolf really just wants people to still believe capitalism – a fairy tale definition of it – serves the interests of the majority?

Are the writers at the Financial Times, The Economist, Foreign Affairs, and the Hoover Institution the modern version of the “secular priesthood?” Yes, but they represent only a minute fraction of the deeply embedded system of propaganda that needs to be dismantled. We all should be asking ourselves, what role do I play; as we are all in some ways complicit, often without even knowing it.

Conclusions and Hong Kong Protests

What does Hong Kong tell us about the relationship between capitalism and democracy? Two recent articles published in Bloomberg this past August tell a compelling story which I feel captures this quite accurately.

As mentioned above Lindberg et. al. (2019) provides us with a brief account of a 28-year-old accountant whose employer expects him to work Saturdays and Sundays, enjoying very little time off, so he can afford the exorbitant cost on his tiny living space, which involves cramming into a subdivided flat among six tenants. The feeling among many other youth workers in the city is a sense of hopelessness for the future. The property issue is a direct consequence of the power of the richest in Hong Kong society whose initial fortunes were made in real estate when they were awarded key government contracts and then leveraged those gains to expand into other sectors. They are highly influential in upholding a conservative government which caters to their interests, while many struggle unnecessarily due to rising rents which goes toward making the moguls and family conglomerates even wealthier. These billionaire moguls are among the 1,194-member election committee which chose Carrie Lam, whom they defend to this day during the ongoing protests. Moguls, such Hong Kong’s richest man, Li Ka-Shing, have called for an end to the protests, because it is hurting their returns. The fact that the protesters are willing to destroy infrastructure and the economy suggests they have little to lose, because they feel excluded in their own society. As with the US interests, these moguls do not care about democracy, unless their financial interests are secure.

In conclusion, what we observe today is a system of global capitalism, which is extractive and weakening existing democratic institutions. If we pay close attention, we can also observe propaganda efforts led by mainstream media to divert attention from the real cause of the democratic decline, while trying to sell capitalism [unironically] as its savior. Many public intellectuals either have not yet awakened to this reality or they have too much skin in the game and they are doubling down to defend what they have. Either way, the system is changing – the public is organizing and resisting and the power structures are becoming more repressive in order to defend their interests. Let’s hope for the more inclusive outcome.

References

- Baker, C & Phongpaichit, P. (2014) A History of Thailand. Third Edition. Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

- Chomsky, N. & Herman, E.S. (1979) The Washington Connection and Third World Fascism: The Political Economy of Human Rights vol 1, London: South End Press.

- Crozier, M.J., Huntington, S.P., & Watanuki, J. (1975) The Crisis of Democracy, Trilateral Commission Report, New York University Press.

- Diamond, L. (2019) Democracy Demotion: How the Freedom Agenda Fell Apart, Foreign Affairs, 98(4), 17-25.

- Einhorn, B., Kwan, S. & Zhao, S. (2019, August 22) Hitting Tycoons Where It Hurts Could Appease Hong Kong Protesters. Bloomberg Businessweek.

- Free Exchange (2019, June 13) How compatible are democracy and capitalism? The Economist.

- Herman, E.S. & Chomsky, N. (1988) Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Johnson, D. (2015, May 27) Stop Calling the TPP a Trade Agreement – It Isn’t. Moyers & Company.

- Kennan, G. (1948) Review of Current Trends, U.S. Foreign Policy, Policy Planning Staff, PPS No. 23. Top Secret. Included in the U.S. Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1948, volume 1, part 2 (Washington DC Government Printing Office, 1976), 509-529. [Accessed 13 October 2019] Retrieved from https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Memo_PPS23_by_George_Kennan

- Kennard, M. & Provost, C. (2016, July 25) Inside the Corporate Utopias Where Capitalism Rules and Labor Laws Don’t Apply, In These Times.

- Lindberg, K.S., Kwan, S., & Curran, E. (2019, August 21) A Generation With No Future Erupts in Hong Kong Protests. Bloomberg Businessweek.

- Magnuson, J.M (2007) Mindful Economics: How the U.S. economy work, why it matters, and how it could be different. New York: Seven Stories Press.

- Orwell, G. (1972, September 15). The Freedom of the Press [Orwell’s Proposed Preface to ‘Animal Farm’] First published: The Times Literary Supplement. [Accessed 13 October 2019] Retrieved from http://orwell.ru/library/novels/Animal_Farm/english/efp_go

- Pilger, J. (Director, Writer, and Reporter), Watt. M. (Producer) (2007) The War on Democracy [Documentary]. Youngheart Entertainment PTY Limited.

- Sen, A. (1999) Development As Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Simpson, B. & Venkatasubramanian, V. (Eds.) U.S. sought to preserve close ties to Indonesian military as it terrorized East Timor in runup to 1999 independence referendum. National Security Archive, Briefing Book #682, published 28 August 2019. [Accessed 13 October 2019] Retrieved from https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/briefing-book/indonesia/2019-08-28/us-sought-preserve-close-ties-indonesian-military-it-terrorized-east-timor-runup-1999-independence

- Supiot, A. (2019, June 18) The World Bank Helps Investors Choose the Law They Want [public lecture], excerpts published by The Real News Network. [Accessed 13 October 2019] Retrieved from https://therealnews.com/stories/the-world-bank-helps-investors-choose-the-law-they-want-1-2

- Wainwright, S. (2019, October 11) Cops aren’t tops. Green Left Weekly.

- Wolf, M. (2019, July 2) Liberalism will endure, but it must be renewed. Financial Times.

- Wolf, M. (2019, September 18) Why rigged capitalism is damaging liberal democracy. Financial Times.

- Yu, V. (2019, October 5) Hong Kong emergency law ‘marks start of authoritarian rule.’ The Guardian.

Notes

- There are five key characteristics (drawn from J. Magnusson) which define a capitalist system. First is the private ownership of property. Second is the profit motive. Third is an integrated system of markets. Fourth is the social separation of ownership and work. Fifth is the growth imperative. The combination of these five factors helps understand how the system works and whom it is designed to benefit – primarily owners and investors. People who have skills and play an institutional role in perpetuating the system will logically be rewarded or compensated accordingly. This is why people find lucrative careers in marketing and finance.

- Alain Supiot, 18 June 2019: “As you may be aware, this belief has led to the World Bank’s “Doing Business” program, which ranks national business regulations according to their ability to meet investors’ expectations. It is a sort of self-service tool which provides investors with a convenient way to choose the regulations that suit them best. The employment section of the “Doing Business” program is currently being reviewed following considerable criticism, but that is only one particularly visible part of a broader evolution in private international law called “law shopping”, in other words, the possibility for large firms, now that borders have been dismantled, to choose for themselves the law that they want to apply. Now if there is one thing we can be sure of it is that you cannot have both “law shopping” and the rule of law at the same time. The rule of law applies to everyone. If you let everyone decide which law suits them best, what you get is not the rule of law but a rule of widespread violence.”

- The threat in Vietnam was not communism per se; it was the threat of a good example – a system which could successfully defy the control of the U.S.. The massive destruction inflicted on Vietnam was meant to serve as a threat to other [small] nations, who might think about pursuing their own national objectives, such as using their resources for their own development, which do not align with U.S. strategic interests. This demonstration effect has been the ongoing strategy throughout Latin America and the Middle East. The economic war that was waged against Vietnam from 1975-1994 was meant to strangle their economy and serve another type of demonstration effect. The devastated economy could then be used as anti-socialist propaganda in an attempt to dissuade the America population from demanding social policies that would undermine elite [investor] interests. This tactic has also been used against Cuba for over fifty years and is currently being waged against Iran and Venezuela.

Thank you for sharing this essay with us. I must say I agree with most of the things you wrote. Yet, even if we have the same analysis, we draw different conclusions.

In the end of the year 1940, blitzkrieg was overwhelming Europe. Then US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) promised an industrial war effort for the Brits. He mentioned the “Arsenal of democracy”. I am fond of this expression: the combination of these two words might seem antithetical. It is not. This theory of instrumentalization of democracy and human rights by the US finds its bosom in the 1845 Manifest Destiny. This has been the cornerstone of US foreign policy for 174 years now.

During the Cold War, this rhetoric took root amongst western nations. The two blocs confrontation was not only ideological. The two models’ confrontation also had a military chapter. The nuclear threat was looming. The containment theory was one way to fight the Soviets grounded influence. In South America, the US “backyard”, but also within Europe and Asia. The US won both the military and ideological wars. They secured their position as the global protector and warrantor of their model.

However, the history did not end (Fukuyama) with the USSR fall and instead, the US kept weaponizing their democracy and human rights protector status to serve their own political and economic agenda. Neither the aim nor the mean to achieve this are good willing from the US. Unilaterally waging a war, nation building, politics meddling in a third country are never legitimate.

The world used to look upon the US but now they have new competitors. The theory underpinning the US legitimacy for asking more democracy and human rights around the world is crumbling. The Chinese model is emerging as one that can combine an open economy without democracy, contradicting US theorical assertions.

In the wake of this threat to western values, the US is needed now more than ever. I believe there are two things that contributed to shun a third world war during the second half of the last century. First, the balance of terror with the nuclear bomb. Second, Pax Americana: meaning the legitimacy of the US leading the Western World.

These are dangerous games, but international relations have always been about war. Politics have always been about confrontation. Felons only understand strength. The stronger the US, the safer the world.