1. Introduction

Sixty years ago, there was no effective way to treat end-stage renal disease. Now that organ transplantation and dialysis are widely available across the US, many Americans who have chronic kidney disease, are offered renal replacement therapy. Research shows that organ transplantation offers a superior quality of life and longevity in comparison to dialysis (Wolfe, Ashby, & Milford, 1999). In the perfect world, an increase in demand would lead to an increase in supply due to the law of supply and demand. However, in reality, the gap between supply and demand has only widened. In 2004 there were around 87 146 people on the organ waiting list, as of 2014 that amount is 123 851 and growing. (OPTN, 2014) Even though evidence states that kidney transplant is best to be performed early on in the course of chronic kidney disease therapy, the waiting time, already stretching up to ten years in some parts of the US, is still increasing. Although in recent years the number of kidneys donated post-mortem has been steadily increasing, the average age of the donors has also increased, which causes issues with the quality of donated kidneys. Gaston, Danovitch, Epstein, Kahn, Matas, and Schnitzler (2006) demonstrate that in reality, even if all potential donors would donate post-mortem, there would still be an organ deficit. Because of the National Organ Transplant Act of 1984, which prohibits donating organs for a financial incentive, there is a shortage of live organ donors. This paper aims to explain that kidney donation in trade for financial incentives would improve the welfare of society and decrease the demand deficit of kidney donors.

Firstly, this paper explains what repugnant goods are. Secondly, it discusses the possible solutions to the lack of kidney donations. Thirdly, it explains how the Law of Supply and Demand affects the kidney market if it were to be made a free market. Finally, it shows the effect legalizing the donation of organs for financial gain would have on society’s welfare.

2. Repugnant goods

On the one hand, there is the example of lending money, nowadays, it is normal that there is an interest percentage. However, a few hundred years ago, this was considered widely repugnant. On the other hand, there is slavery, this, for example, used to be legal but is now considered repugnant. This is due to the fact that times change, and so does society’s look on certain norms and values. When a majority of people in a society think that not only themselves but also others should not use/buy/participate in said good/activity, these goods/activities can become illegal. Even though there may be a set amount of suppliers and demanders, there will be a restriction on these transactions because a majority sees it as: inappropriate, unfair, distasteful, undignified, or unprofessional (Roth, 2007). Not all markets are completely repugnant, some markets are also partially repugnant, examples of this are pornography and prostitution market. These markets are limited or banned in some places, but as long as both parties are accepting the transaction it is legal. Kidney donation is seen as a noble and charitable thing to do, but selling kidneys, however, is regarded as unethical and selfish nowadays. This may be because lots of people see it as an objectification of the body when it is used for financial gain. However, Pope John Paul II even wrote in his encyclical letter Evangelium Vitae, that the donation of organs is a praiseworthy act.

3 The kidney market as competitive market

3.1 Possible solutions

It is a known fact that there is a great shortage of kidney donations. There are only two options to eliminate this problem. The first is to reduce the demand for kidney donors. A possible solution could be a stricter criterion so that the number of patients would match the number of donors every year, but this would lead to another ethical dilemma; who prioritizes over who. Another possible solution is the increase in the usage of dialysis. On the one hand, this may seem like a good solution. On the other hand, this goes paired with large costs. (Cecka, 2005)

The other possible solution is to increase the supply of kidneys. Due to the near-future unlikelihood of xenografting, the only way to substantially change the number of donated kidneys is by a major increase in the donations from living donors. Since even if all deceased people would be donors there still would be a deficit. (Gaston, Danovitch, Epstein, Kahn, Matas & Schnitzler, 2006)

3.2 Perfectly competitive markets

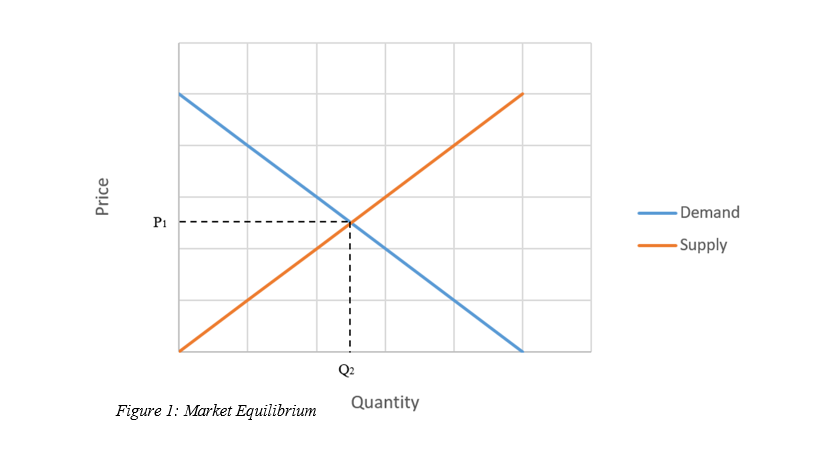

Acemoglu, Laibson, and List (2016) state that in a perfectly competitive market, an individual buyer, or seller, is not capable of influencing the price. “Competitive markets converge to the price at which quantity supplied and quantity demanded are the same.” (Acemoglu, Laibson, & List, 2016, p. 116) This point is called the market equilibrium. The market equilibrium is displayed in figure 1.

In this figure, P1 represents the price under which supply and demand are equal. Q2 represents the quantity under which the supply and demand are equal. When the price of a product is higher than the market equilibrium, there will be a supply excess. Because of the excess, prices will go down until they reach the competitive equilibrium. (Gale, 1955)

3.3 Current situation

The current situation of the kidney market, however, is far from perfect, there is a great excess demand. This demand deficit is due to the lack of donors. According to the Law of Supply, the higher the set price, the higher the supply will be. In the current situation, there is no financial compensation for the donation of an organ since that is illegal. Because of this many people might not donate their kidneys. Figure 2 displays the current situation where the demand greatly exceeds the supply.

3.4 Current Loss of Welfare

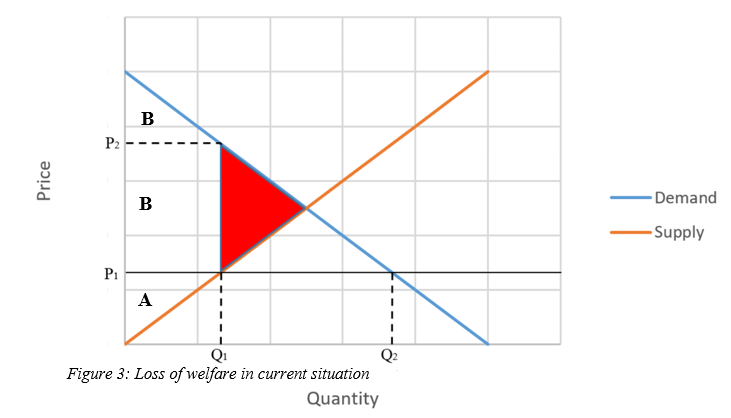

Acemoglu, Laibson, and List (2016) state that when market distortions occur which negatively affect the social surplus, the decrease in social surplus can be measured by finding the deadweight loss. Furthermore, they state that by maximizing the social surplus, society’s welfare will also be maximal. Figure 3 displays the loss of welfare in the current situation.

The red triangle (Figure 3) displays the current loss of welfare. The producer surplus is represented by B and the consumer surplus is represented by A. (Acemoglu, Laibson, & List, 2016) In an optimal situation, the social surplus would be the entire triangle, thus A, B, and the red triangle. However, due to a set price, the current social surplus is A+B. This shows that it could possibly be in society’s best interest to make the kidney market a free market because it increases the social surplus.

Not only the loss of welfare displays the benefits of making the kidney market a free market. A successful kidney transplant comes with major financial benefits. Not only to the beneficiary but also for society. Matas and Schnitzler (2004) calculated that the average living donor transplant saved the taxpayers a minimum of $94 000 over the average lifespan of the beneficiary in comparison to the cost of maintenance dialysis. Furthermore, it is estimated that the improvement of the quality of life would be equal to $50 000 per year per patient when undergoing an organ transplant in comparison to maintenance dialysis. Combine this with the previously noted savings, and the average kidney transplant (if the beneficiary lives for at least 9 years) will be over $500 000 (Cecka, 2005)

4. Conclusion

By making the kidney market a free market, it could be possible to severely reduce the waiting time on the donor list due to the increase in supply. Furthermore, it greatly increases societies welfare by getting rid of the deadweight loss which comes with the fixed price. Additionally, it could save taxpayers up to $94 000 per successful transplant. And most importantly, it might save lives, something you can’t put a price tag on.

References

Acemoglu, D., Laibson, D. I., & List, J. A. (2016). Economics. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

Cecka JM. The OPTN/UNOS renal transplant registry. In: Cecka JM, Terasaki PI, eds. Clinical Transplants 2004. Los Angeles: UCLA Tissue Typing Laboratory, 2005:1–15.

Gale, D. (1955). The law of supply and demand. Mathematica Scandinavica, 3, 155. doi:10.7146/math.scand.a-10436

Gaston, R. S., Danovitch, G. M., Epstein, R. A., Kahn, J. P., Matas, A. J., & Schnitzler, M. A. (2006). Limiting Financial Disincentives in Live Organ Donation: A Rational Solution to the Kidney Shortage. American Journal of Transplantation, 6(11), 2548-2555. doi:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01492.x

Matas AJ, Schnitzler M. Payment for living donor (vendor) kidneys: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Am J Transplant 2004; 4: 216–221.

Roth, A. E. (2007). Repugnance as a constraint on markets. Boston: Division of Research, Harvard Business School.

The Need Continues to Grow – OPTN. (2014). Optn.transplant.hrsa.gov. Retrieved 13 March 2020, from https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/need-continues-to-grow/

Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL et al. Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 1725–1730.