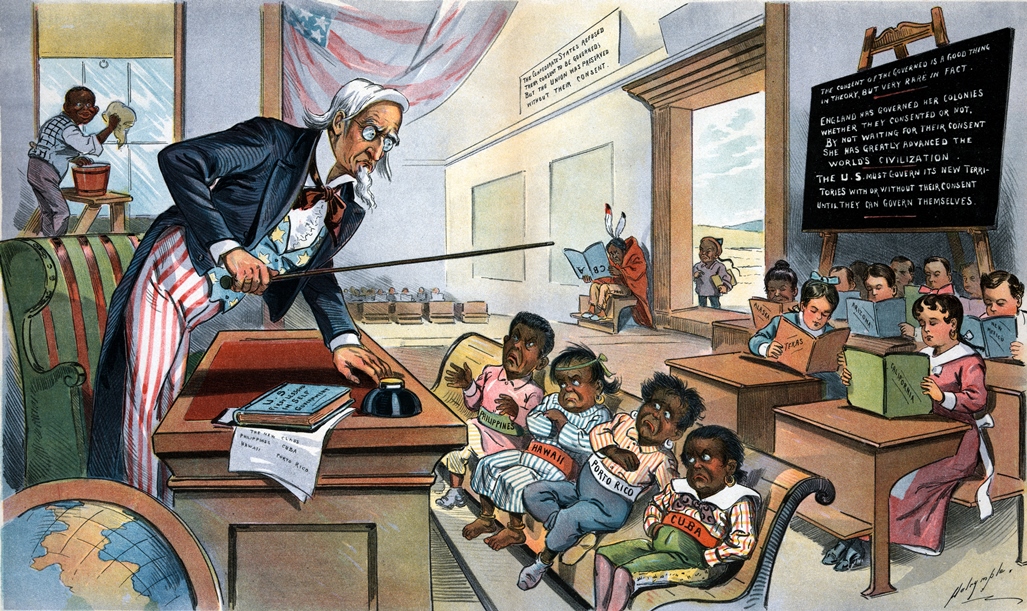

Cover Photo: “School Begins” (Puck Magazine 1-25-1899, now in the public domain). Caricature showing Uncle Sam lecturing four children labelled Philippines, Hawaii, Puerto Rico and Cuba, in front of children holding books labelled with various U.S. states. A black boy is washing windows, a Native American sits separate from the class, and a Chinese boy is outside the door.

Volume 2, Number 1: March 2019 | Editorial

What is the American model? It can be summarized by three key factors: deregulation, weak unions, and a minimalist welfare state. When it comes to models of development, what constitutes development is a matter of normative discussion. It should be easy to understand that the business and investment community has a different set of ideals for development than the average working class citizen. Even among scholars there is disagreement regarding the development objectives. I argue that the American model of “development” is inappropriate for most nations to follow for three reasons: it requires the capacity for empire building (militarily and economically), which most nations do not have; it is not sustainable (socially or ecologically); and due to systemic reasons, it falls short on many important indicators (such as health and education), despite having one of the highest per capita incomes in the world. This article will focus on a short history of American empire in order to argue that empire building capacity is limited to a few and, therefore, the success of the American model – whatever that may be – may not be applicable to other countries trying to follow in its footsteps.

Due to what many recognize as achievements in areas such as average material living standards, political freedom, technological innovations, arts and entertainment, military strength, and powerful multinational corporations; some economists and politicians, but primarily business elites in the advanced nations, applaud the United States as a model for development – a pinnacle of success that other nations, both developing and developed, should aspire to emulate. International institutions, such as the IMF and World Bank, have historically taken pages from the American handbook in devising their policy approaches.

While pretty much any nation can follow the path of the American model with respect to deregulation, weak unions, and a minimal welfare state, one critical aspect that sets America apart from many developing countries, yet is often omitted from the discussion, is its empire-building capacity. Like many of the advanced nations before it who benefited significantly from empire, such as the Spanish, French, and British, the United States has developed over nearly two centuries, although not exclusively, due to significant benefits from empire – with the Monroe Doctrine in the 1820s serving as a defining moment in U.S. foreign policy, effectively stating that the entire Western hemisphere was America’s domain.

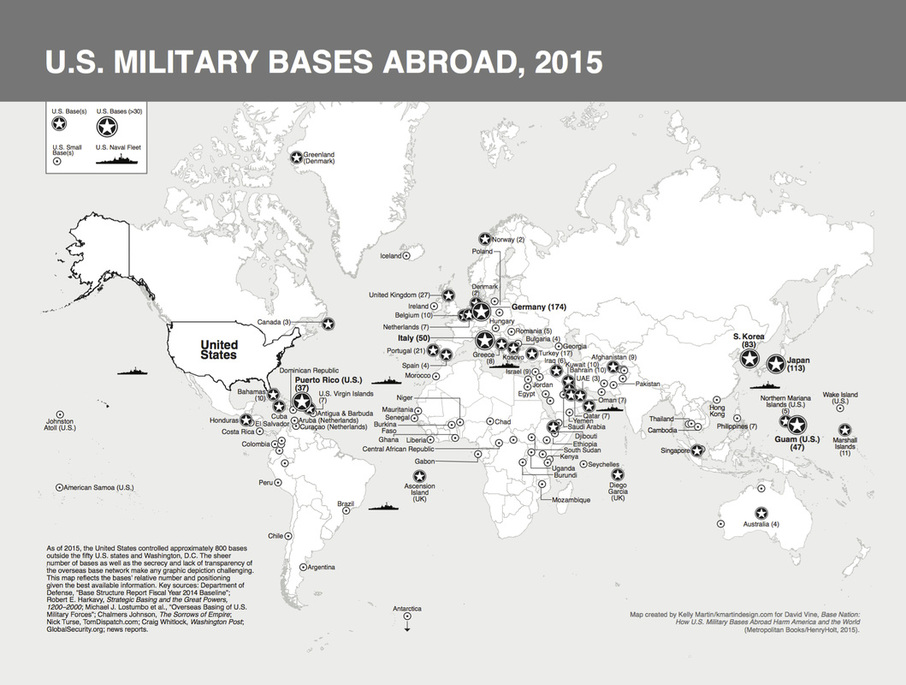

While I will not be able to go into the full history of American imperial pursuits, we can begin with the countries of Latin America acting as a service area for American business interests. Although not explicitly imperial as the Spanish, French, and British empires, for example, it took the form of “anti-colonial” imperialism, which resembled protecting the countries of Latin America from European imperialism on the surface, but exercising significant influence on internal affairs and even control through a variety of indirect channels. It can be safely argued that empire was driven by trade and industry, primarily for the benefit of large corporations like Dole bananas and United Fruit, just to name a couple. At the time of the Monroe Doctrine, the U.S. military was weak, so it depended upon British support, but it grew in strength and influence over the following two centuries, effectively serving as a private security force for U.S. business interests abroad. The U.S. global reach significantly expanded following World War II, both economically, with the Bretton Woods system, and militarily, with the dramatic expansion of bases, some expansion involving the expulsion of indigenous populations, for example, of the Marshall Islands for the purpose of nuclear weapons testing in the 1940-50s and of Diego Garcia in the Chagos Archipelago in the early 1970s for building a key military installation in the Indian Ocean.

In the bipolar world order which emerged following World War II, much of the Cold War was carried out in peripheral states through a series of alliances, proxy wars, and military interventions. The United States was able to secure more of their global interests, all under the banner of halting Soviet imperialism and resisting the “communist threat.” The United States established itself as the sole hegemon following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Most Americans fail to recognize their country as an empire, probably because, unlike previous empires, American empire was mostly clandestine, it had always been carried out under the guise of anti-imperialism, starting with the Monroe Doctrine. Furthermore, the education system in the U.S. does not introduce students to the primary methods of influence used by a clandestine empire, such as operating through unpopular puppet regimes, which would not survive without U.S. support; CIA-sponsored coups of democratically-elected leaders that resist American interests; and direct military conflicts, which are always portrayed as defensive, rather than offensive.

So if the United States acts as an imperial power, who benefits from this position? While the average American citizen receives some ancillary benefits in terms of defense from foreign invasion, the primary beneficiaries are the members of an elite investor class throughout many of the advanced nations of the world and, in a globalized capitalist system, elites in the developing countries with strong ties to the West. While the American soldier today is paid to serve, prior to abolishing the draft, it is a little more than ironic that the American government had to compel citizens by threat of imprisonment to go overseas and fight in horrific conditions for “others’ freedom,” such as in the “defense” of South Vietnam, in what were actually neo-colonial conflicts. This conflict was simply an extension of the post-war plan of expanding the market area of Western capitalism, which involved helping France re-colonize its former colony in Indochina, which they held until 1954. The Vietnamese conflict in the eyes of the Vietnamese was a fight for independence and America, supporting an unpopular client regime in the South to maintain a foothold in the region, was an unwelcome occupying force in a long line of foreign occupiers from the Chinese, to the French, and the Japanese. Meanwhile, American propaganda would teach people to view the Vietnamese as an enemy to be feared and one that must be defeated, while actually the farmer in rural America arguably had more in common with the farmer in rural South Vietnam than with the rich investors in the Hamptons on the East Coast, yet, both farmers were brought together to fight. For what? Have the gains from such conflicts gone to the benefit the average, working-class American? If one views the world in the context of a “core-periphery” model of dependence theories with the class corrective, with individuals instead of the nation state as the units of observation, these types of conflicts and imperial activities become easier to understand. This places the United States in a unique position, globally, in which it supplies military personnel and equipment from the ranks of working class Americans and taxpayers, respectively, to defend the interests not of American citizens, but rather the interests of a global core of an elite business and investor class.

The United States benefits from its position of global power in a couple other ways: having English as the international language of business, from which average Americans certainly benefit, and having the U.S. Dollar as the global reserve currency – something many countries covet, but cannot apply to their situation. It has been alleged that the U.S. invasion of Iraq among other forays has demonstrated their willingness to go to war to defend the status of the Petrodollar, which is something that often goes unmentioned. Recently there have been attempts to de-dollarize by both China and Russia. This taking place under an ongoing trade war between China and the U.S.

However, with enormous global power economically and militarily, with over 800 bases around the globe, the United States finds itself, at least for the time being, in the unique position with an ability to exercise its wishes in many ways in the global arena. The “rule of law” does not seem to apply to the United States when it comes to international cooperation as evidenced by its disregard for multilateral agreements on trade, international law, and action on climate change mitigation; and by invading other countries as in the cases of Vietnam, Grenada, Afghanistan, and Iraq. With the power to influence international organizations, like the IMF and World Bank, the U.S. has preached efficient market principles to the developing world, while following protectionist policies and relying on the state for innovation and development, as well as agricultural subsidies. Furthermore, when the U.S. imposes sanctions or embargoes on countries they seek to punish, other countries in the world follow orders, out of fear of reprisal from America. Cases include the commercial, economic, and financial embargo placed on Cuba since 1958; the economic blockade placed on Haiti from 1991-1993 under Clinton; the near-total financial and trade embargo on Iraq from 1990-2003, and the blocking of food aid to Vietnam and the [unrecognized] People’s Republic of Kampuchea (Cambodia) in the late 1970s, which led to a massive famine. In the end, the business and banking elites which dominate the economic system have succeeded in privatizing profits, while socializing risks and costs.

So far I have tried to make the case that the American development has been based on certain advantages that only a few countries can emulate. China is clearly in a similar position as the United States in terms of empire-building capacity and it seems we are entering into a period of a new Cold War between China and the United States. It remains to be seen how this will play out. Now the Chinese and America models differ on a number of fundamental levels, primarily politically, but this piece is not going to address the Chinese model. While the Chinese may perform better than the Americans in some aspects of development – and I can certainly give credit where credit is due – this is not an endorsement of the Chinese model either; as many of the same criticisms, plus additional ones, apply.

In conclusion, while I accept that Americans have achieved high relative standards of living on average and have enjoyed numerous freedoms compared to other countries, I argue that America is an inappropriate model of development because, quite simply, it is an unsustainable model built on empire, which many countries cannot emulate, nor, in my view, should they. American foreign policy is driven by a business-dominated political-economic system with less emphasis devoted to health and primary education, which are arguably two of the most important development indicators. This is consistent with a capitalist-oriented economy, which places investor interests above the interests of the working class, the poor, and the environment. Many of the institutions are established with this primary focus, both politically and economically, thanks to powerful interest groups and concentrated economic power. While this may be a good system for accumulating profits for investors; for the stated goals of development, it falls short in many categories and is even experiencing a reversal of some progress achieved by the middle classes throughout the twentieth century. I will have to expand on these points in a future piece. Unfortunately, any alternative system that may be successful will challenge the U.S.-dominated global system and will have to be dismantled as has been done repeated throughout history. The real threat all along was not communism; it was the threat of a good example and of national independence movements that pursued their own interests, such as using domestic resources for the good of their own people.

For an updated list of bases used to create this map, see: http://dx.doi.org/10.17606/M6H599